Battlefields and Ghost Towns

Hey Guys! We spent one week in the Dillon, MT area as we were making our way up to Glacier National Park. This stop was basically just a big hopping point between Ketchum and West Glacier, but I chose it specifically so we could visit Big Hole National Battlefield and Bannack State Park. I figured…we might as well make the best of the week, right? Let’s stop someplace where we can continue our National Park Tour.

Every single National Park Unit tells a story. Battlefield stories are usually hard to hear, but I feel like they need to be remembered. History should never be forgotten…our history reminds us of how far we’ve come and how far we could fall if we make the same mistakes. Learning our history…all of our history…not just the history that’s pretty or makes us feel good… helps keep us from making those same mistakes again. We’ve learned. We’ve grown. Let’s not forget it.

Every story has two point of views. We’ve found that the National Park System is excellent at portraying both sides of the story equally and without prejudices. Our school system could learn a thing or two from the National Park System about teaching the true history of our country.

Like so many battlefields, Big Hole National Battlefield is considered a sacred place…a place where blood was spilled and life was extinguished. This National Park Unit tells of the battle between the Nez Perce (nimí•pu) and US Army troops. But really, it’s the story of the Nez Perce’s struggle to survive. The Nez Perce can trace their heritage and their life on the land back 9,000 years. They were one of the biggest tribes in the US with around thirteen million acres of land spanning across what is now Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and up into Canada. As the US struggled to find it’s footing as a new nation, the Nez Perce lost most of their land and conflicts began to occur.

In 1855 the US government proposed a treaty. The Nez Perce would give up over half of their traditional lands to the growing US nation but they would still keep the right to hunt, fish, and gather on those lands. Everything seemed to work for five years, but then gold was found which led to an influx of over 15,000 miners and settlers and once again conflicts started to occur.

In 1863 the US government met with all of the leaders of the different Nez Perce bands to try and come to an agreement that would cut the Nez Perce lands by another ninety percent and the Nez Perce would go live on specified land reservations. During the meetings the leaders of five bands were so disgusted by what they were hearing, they got up and left the meetings. The meetings didn’t stop though. They continued with the leaders who stayed and in the end the leaders who stayed agreed to the treaty because it didn’t affect their bands as much. Those leaders signed the treaty for all Nez Perce…even the bands who had left the meetings. The bands who left refused to acknowledge the new treaty and would become known as the non-treaty Nez Perce.

The US government gave the non-treaty Nez Perce thirty days to move onto the reservation or they would be put there by force. The Nez Perce had lived on this land for thousands of years and didn’t see what gave the US government the authority to tell them where they should and shouldn’t live. In the end, the non-treaty Nez Perce gave in and started the long process of gathering all of their things and livestock to make the journey to the reservations. Before they could reach their destination though, conflict and fighting broke out as they were going through land that had once been theirs, but had since been claimed by settlers. This started the the long chain of events that would be known as the Nez Perce War.

On August 7, 1877 around 800 non-treaty Nez Perce made their way to a place they knew well from past buffalo hunts. They called it The Place of the Buffalo Calf (Iskumtselalik Pah). They knew there would be fresh water, a big field for their horses to graze and the nearby forest would provide trees for the tipi poles. They had been relentlessly pursued… fighting and fleeing for several long weeks and they were all weary and worn. The leaders of the five non-treaty Nez Perce bands believed that by moving across the Idaho border into Montana that they would leave the war behind.

The next day, August 8, they spent the day setting up camp. Eighty-nine tipis were set up throughout the field. They spent the day hunting and gathering food and water, looking after their tired horse herds (close to 2,000 horses), and planning the next step.

In the early morning on August 9, a Nez Perce elder went down to the river to check on some horses. What he didn’t know, was that during the night the US Army, led by Colonel Gibbon, had caught up with them and was positioned for an ambush at the river front. What happened next was pure chaos. One of the military volunteers got itchy and shot the elder. The Nez Perce woke to gunshots and screams. At one point soldiers started setting fires to tipis with women and children hiding in them.

I should point out that this particular unit of the US Army had just come from Little Bighorn where they saw what was left of Custer and his unit (not much). They were worked up and scared for their lives. Most of this unit was new to fighting. I don’t think you can ever really justify the brutality of what they did though.

When it was over, 90 Nez Perce and 30 military/civilian volunteers had been killed. The US Army had expected the Nez Perce to be surprised and to quickly surrender, but that’s not what happened. The Nez Perce fought back to protect their families and pushed the military back across the river and up the bank. The military retreated and dug shallow rifle pits to hole up in. Several Nez Perce volunteered as sharp shooters to hold the US military troop pinned down so their families could quickly do what they could for their dead and then flee.

After the sharp shooters left, the unwounded soldiers did their best to help the injured. There wasn’t a doctor and they really weren’t sure if the Nez Perce would come back or not. With no medical supplies, equipment, clothing, or food Colonel Gibbon decided to camp where they were until reinforcements could arrive.

This was just one battle in the Nez Perce War. From Big Hole, the Nez Perce eventually made their way up to the Canadian border where some of them crossed over and continued to fight and some chose to stay and surrender. It had be a long hard journey stretching over 126 days and close to 1200 miles that spanned over 4 different states. Today, the Nez Perce visit the Big Hole Battlefield to honor the memories of those who were killed on August 9 and 10 of 1877.

We only spent a few hours at Big Hole Battlefield, but what we learned will stay with us for the rest of our lives. We remember and we honor all those who fell.

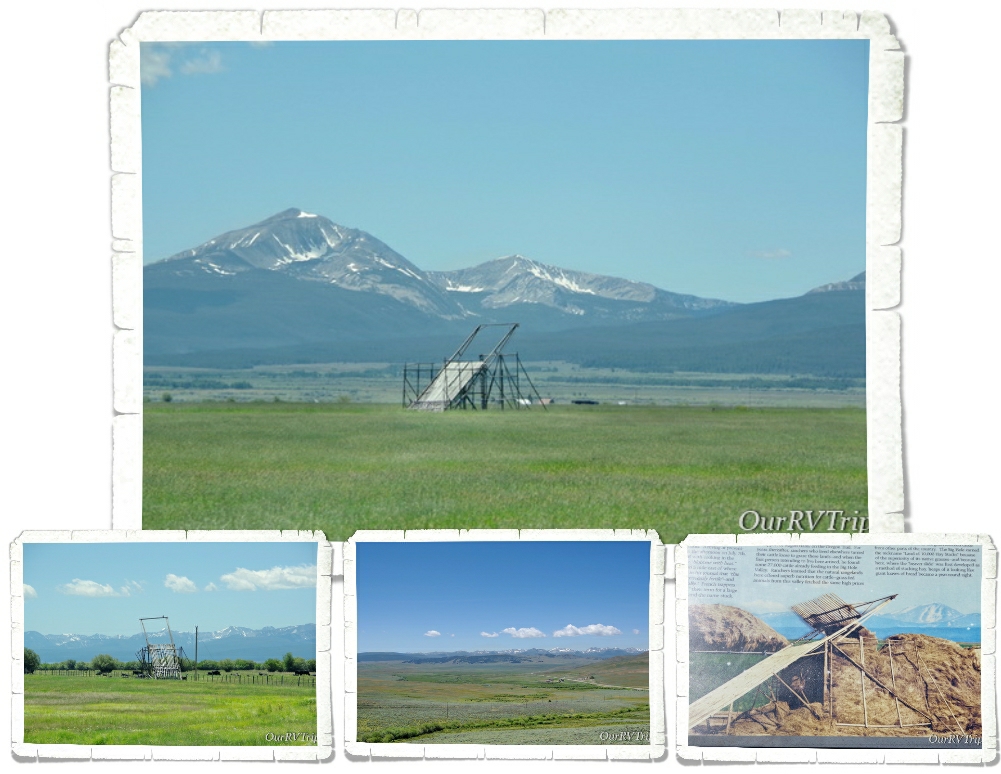

On the way to Big Horn Battlefield, we kept seeing these unusual structures out in the fields. Being the inquisitive nerds we are…when we got to the National Park unit, we asked a Ranger if she knew what they were. Luckily, she knew exactly what we were trying to describe. Which…look at that structure, how would you describe it?

They’re called beaverslides. Yup, you read that right. A beaverslide is a hay stacker. Invented by two ranchers in the Big Hole Valley in 1910, the ranchers of this valley used them to stack hay up to 35 feet high and contain close to 20 tons of hay so they could feed their cattle from it all winter. There was a time when the Big Hole Valley was known as the Valley of 10,000 Hay Stacks. Most ranchers in the valley have switched to more modern methods, but there are still a few who are using the beaverslides.

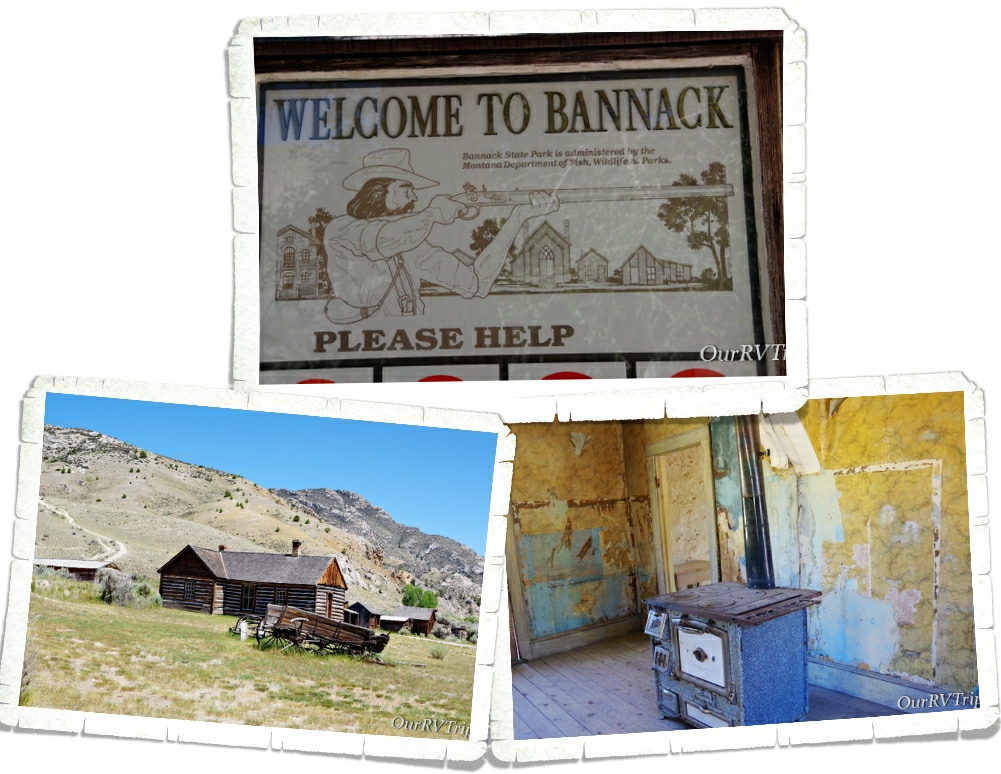

The other place we wanted to explore while in the Dillon area was Bannack State Park. Bannack is said to be one of the best preserved ghost towns in the US. We’ve been to our fair share of ghost towns and I have to agree. Bannack is the best we’ve seen.

One of the best things about this ghost town is that you actually get to go into the buildings. And I don’t mean go in and look through some plexiglass at a few decorated rooms…nope…you can actually go in and explore. The Hotel Meade was one of our favorite buildings to go through. We were able to go through the rooms downstairs and then venture upstairs to see most of the actual rooms that guests stayed in. They’ve been left alone, but preserved…if that makes sense. Montana Fish and Wildlife oversees Bannack and has done an excellent job of keeping the buildings authentic but as safe as possible. Quite a few buildings had a sign at the entrance that warned people to enter at their own risk. They are old buildings…

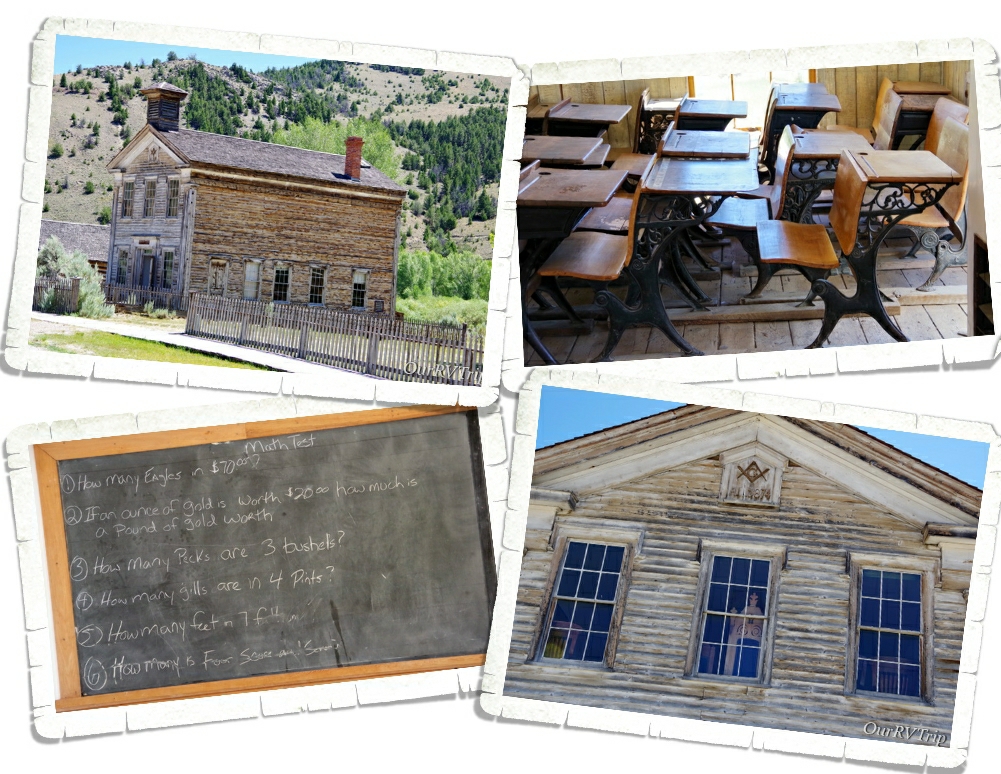

This building, built in 1874, served as both a school and the Masonic Lodge. The first floor was used as a public school for grades K-8th while the second floor was used as Masonic Lodge Number 16. We were able to go into the first floor school, but the second floor was closed off the day we went.

Like so many towns of that time, Bannack (named for the Bannock Indians who frequented the area) started as a mining camp when gold was found in July of 1862 at the nearby Grasshopper creek. The camp grew from around 400 people that fall to over 3,000 people the next spring. During the winter of 1862, Governor Sidney Edgerton named Bannack the first capital of the Territory of Montana. The Post Office was established in November of 1863.

And, like most mining towns of that time…Bannack wasn’t a safe place…especially after dark. We found a hidey hole in the floor of every building we went into. And…there was a rumor that Sheriff Henry Plummer and his posse were actually a gang of thieves and murderers called “The Innocents”.

Most people came to Bannack to find their fortunes in gold mining. Some, came to start businesses like butcher shops, saloons, craftsmen, and ranching. Any supplies had to be brought into Bannack from a great distance and at a pretty big expense. While the town of Bannack wasn’t exactly hard up for money…the residents found that most of their earnings were going to the high cost of goods and services. $500,000 in gold was mined in the area by the end of 1862.

When World War II started, all non-essential mining was prohibited. Bannack’s existence was dependent on the mining of gold. Mining did start back up as soon as the war was over, but the price of gold was so low that the mining town couldn’t survive. People went elsewhere to find jobs and by the late forties, most of the population had moved on. The Post Office closed in 1938, the school closed sometime in the early 1950s and just like that the mining town of Bannack became a ghost town. The gold rush is over, but the spirit of the old west can still be found at Bannack State Park.

We spent a few nights trying to see the Neowise Comet that was visible at the time. We were so far north and the comet was so bright that we didn’t have to wait too long each evening to try and spot it. We think we saw it one night. I circled it in the right picture…It’s not the best shot, but it’s all I got.

Our week flew by. We didn’t really do much of anything else since we’re still trying to avoid going out too much. We mainly just go get groceries and stay home…when we’re not out adventuring in the wild places.

See y’all down the road!

#NationalParkTour